Airway Fire

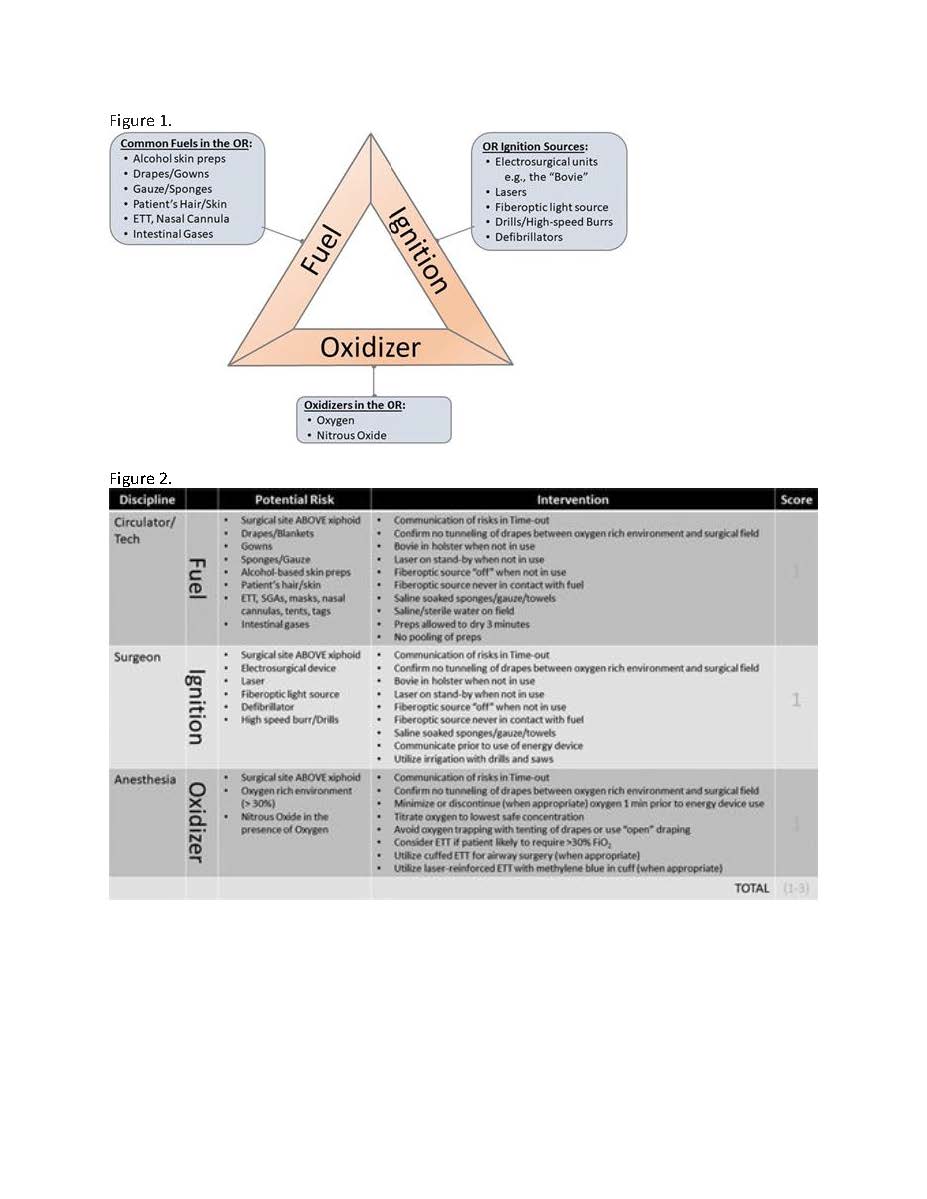

A surgical fire is a rare but often devastating event, with an incidence between 500-700 cases per year and a high likelihood of underreporting1. The operating room is a unique environment allowing all elements necessary for a fire (i.e. oxidizer, ignition/energy and fuel) to be utilized in close proximity (Figure 1). Recognition of contributing factors as well as proficiency at management strategies are necessary to mitigate the risk of generating a surgical fire as well as any subsequent damage should one occur.

Prevention starts with recognition of an elevated risk for surgical fire. The Anesthesia Closed Claims Analysis group recently identified trends from 200 operating room fires2. Most surgical fires occurred during monitored anesthesia care (MAC), and the incidence has been increasing yearly. Electrocautery was the ignition source in 90% of fires, and the source of oxidizer was often oxygen administered openly onto the field. Any procedure that involves the airway or is cephalad to the xyphoid process is at increased risk for airway fires3. The use of a preoperative checklist for procedures with an elevated risk for airway fire is recommended4. Of note, airway fires can still occur if there are gases (such as methane) remaining in the GI tract5. The latter was associated with the use of mannitol-containing colon preparations, and for that reason these preps have been discontinued.

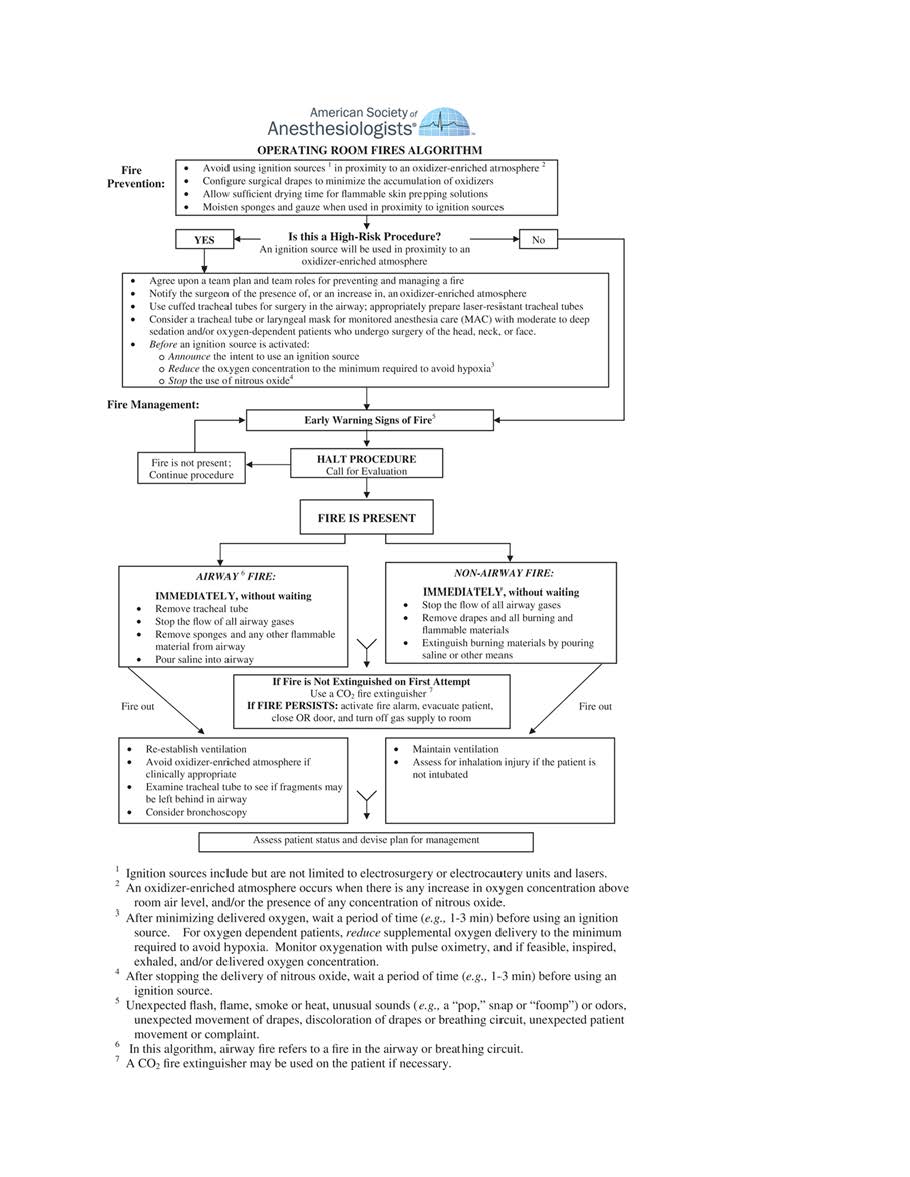

When an operating room fire occurs intraoperatively, the immediate management involves eliminating the factors that lead to combustion. The triad of oxygen/oxidizer, ignition source/energy, and fuel must be addressed simultaneously4,6,7. Both oxygen and nitrous oxide can oxidize and are highly combustible. Of note, nitrous oxide has nearly the same oxidizing potential as oxygen; therefore, administering a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen is almost equivalent to an FiO2 of 100%8,9. As a preventative measure, the current recommendation by the Joint Commission and the Emergency Care Research Institute is to maintain FiO2 at less than 30% in cases with open oxygen delivery (e.g. nasal cannula for moderate sedation or monitored anesthesia care) or when the potential for a surgical fire is a concern4,10. It is important to be cognizant of unexpected regional increases in oxygen concentration during cases with open delivery of oxygen secondary to partitions created by surgical drapes and covers7,11. In head and neck surgeries where closed systems are utilized to deliver oxygen, such as those encountered when using cuffed endotracheal tubes (ETT), the recommendation to maintain FiO2 below 30% stands, as leakage around the ETT cuff or damage to the cuff is still possible4. This applies to both normal as well as laser resistant ETT. The optimal time required to adequately decrease the FiO2 before electrocautery should be used is not established, but the ASA suggests discontinuing high FiO2 at least 60 seconds to 10 minutes prior to initiating use of surgical energy7.

As mentioned previously, the most common ignition source is surgical cautery with the most common culprit being monopolar radiofrequency energy, which includes the colloquially known “Bovie.”12,13 Nonetheless, monopolar energy comes in many forms, including radiofrequency ablation catheters as well as argon plasma coagulators. Although monopolar radiofrequency is the most cited in operating room fires, bipolar energy despite being contained between the two tips of the instrument can still initiate a fire. In addition, ultrasonic devices have also been implicated in operating room fires. The latter can raise temperatures in tissue to greater than 200 degrees Celsius4,14. The second most common source of energy implicated in operating room fires is laser, most utilized in head and neck surgeries. Finally, another well-known energy source is the fiberoptic light used in laparoscopic and robotic surgery. The cord that supplies the light can be inadvertently left on surgical drapes and induce a fire.

Anything flammable can act as fuel for propagation of the fire once oxygen or nitrous oxide is ignited. Importantly, all common materials used intraoperatively can become fuel for a fire once the oxygen content is greater than 30%4,8,15. Common culprits include but are not limited to surgical drapes and gowns (be it paper or cloth), surgical sponges, alcohol-based skin antiseptic solution, and endotracheal tubes4,7,13,15. The latter is most often constructed with flexible polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is highly flammable with a O2 flammability index of 0.26 implying that they are flammable at an FiO2 of 26% in experimental settings8. The same can be said of most catheters used during surgery or the conduct of anesthesia. One must also be cognizant of patient organic sources, such as hair and tissue.

In this context, when a surgical fire is witnessed or suspected, several actions need to be taken simultaneously16. Surgery should cease with no further use of surgical energy. Oxygen delivery and airway gas flow are discontinued. When dealing with an airway fire specifically, the ETT should be removed immediately with saline or water subsequently poured into the airway. There is the historical question of whether saline should be poured into the ETT prior to extubation; however, according to ASA guidelines, immediate extubation is the most appropriate action as the ETT itself can cause further thermal injury. For a non-airway fire, water or saline should be poured on all fires on the patient. All burning materials should be removed from the patient, followed by extinguishing of the flames with water or saline. Once the fire has been extinguished, attention should then return to the patient and respiratory support should be administered with room air preferably, as continued high temperatures can reignite high FiO2. This approach should be a multidisciplinary effort involving the whole operating room, with nursing, surgical and anesthesiology teams working simultaneously towards termination of the fire triad. Last but not least, conventional fire extinguishers (i.e. ABC dry chemical extinguishers) should never be used on or in a patient, and fire blankets have the potential to exacerbate the fire on the patient by concentrating the heat and oxygen. As a last resort, CO2 extinguishers may be used on the patient, as they completely dissipate and do not leave a residue. The ASA provides a succinct flowchart that outlines the management of intraoperative fires (Figure 3) 7.

Once the airway has been re-established via mask after an airway fire, an assessment of the extent of injury as well as potential retained material should be made. This may include laryngoscopy to assess the upper airway as well as bronchoscopy to assess the tracheobronchial tree. For any fire, an assessment of the patient’s whole body should be performed, with application of dry sterile dressing over affected areas. One should be vigilant for the possibility of developing inhalational injury in the patient as well as OR personnel7. For those with extensive burn injuries that meet the American Burn Association’s criteria, consideration should be given to transferring the patient to a specialized burn center 16.

Although brief, the extent of injury from airway fires can be significant, with the potential to affect the whole tracheobronchial tree. As with all burns, airway fires increase the risk of infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, airway obstruction/stenosis, and parenchymal infiltration from inhalation of toxic byproducts of burning material. Sequelae of an airway fire can range from no lasting injury to extensive burns leading to prolonged intensive care unit stays, additional surgery, and death.

- Institute, E. "New clinical guide to surgical fire prevention. Patients can catch fire--here's how to keep them safer." Health Devices 2009;38(10): 314-332.

- Mehta, S. P., et al. "Operating room fires: a closed claims analysis." Anesthesiology 2013;118(5): 1133-1139.

- Rogers ML, Nickalls RW, Brackenbury ET, Salama FD, Beattie MG, Perks AG. Airway fire during tracheostomy: prevention strategies for surgeons and anaesthetists. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001 Nov;83(6):376-80.

- Jones TS, Black IH, Robinson TN, Jones EL: Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology 2019; 130:492–501

- Johnson OC, Feczko BM, Nadig AF, White DM: Theatrical fire pursuant exploratory laparotomy. J Surg Case Rep 2016;6:1–3